The walls of the niches of these two tombs are each divided into two registers:

the upper register is devoted to the myth of Osiris, the lower to that of Persephone The upper frieze of the tombs’ back walls shows the lustration of the mummy ( the death of Osiris, though it may as likely refer to the death of the inhabitant of the sarcophagus assimilated to the deity). Below is a scene of the abduction of Persephone, a scene frequent in Roman-period tombs throughout the Empire, regardless of the gender of the deceased. The left wall of Tomb 2, and almost certainly the right wall of Tomb 1 (the lower part is destroyed by the robbers’ cut), present two more scenes – the upper interpreted as the resurrection of Osiris and, below, the anodos of Persephone partly risen from the earth, having finally been discharged from Hades for six months of the year. The latter is a scene rarely visualized in Greek or Roman art and almost unknown in sepulchral context elsewhere.

The Pronaos of the Main Tomb

The pronaos is introduced by two columns set between antae, but these antae are egyptianized . They take the form of engaged pilasters carved with papyrus at their foot and crowned with anta capitals in Egyptian composite form. Similarly egyptianizing, the columns rise from disc bases and, following the scheme of the antae, terminate in Egyptian composite capitals, which carry the heavy impost blocks that characterize Egyptian architecture. The reliefs carved on the architrave are egyptianizing, too, showing a central winged sun-disc flanked by a Horus falcon to either side. And, though discordantly, the architrave is capped by a row of Greek dentils, the facade is finished off with an Egyptian segmental pediment with a disc centered in its tympanum. In addition to the dissonant dentils above the architrave, another Graeco-Roman architectural element precedes the pronaos. It is a large, plastic, semicircular Tridacna-shell-shaped conch carved in the stone above the short staircases leading to that level, echoing the half-domes of the exedrae and visually tying the facade of the Main Tomb to the catacomb's entrance.

Set in niches capped with plain cavetto moldings and facing one another across the pronaos of the Main Tomb, two almost life-sized statues – one of a female, the other of a male – must be images of the tomb's patrons . These statues are in the tradition of Roman tomb-statues, and their heads are carved in Roman style. The male has snail-like curly hair arranged above a countenance that shows a plastic treatment of his furrowed brow, the hollows under his eyes, his bony cheeks, and the deep groove and ridges that form the nasolabial fold. The pupil of his eye is drilled out, affording him a piercing gaze. The female's head also assumes a Roman-portrait form, and her hairstyle – the locks pulled to either side forming neat waves – is found in many classicizing works from the Greek Classical period to the Late Antique. The two portrait heads, nevertheless, suggest a date in the latter part of the first century ce for the tomb.

Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Male Statue

Yet though the male and female's portrait heads conform with those in Rome, their stance and garments immediately distinguish these statues from tomb portraits from the capital. Both figures stand with their weight evenly divided between both legs in stiff poses that have their genesis millennia past in Egypt, and instead of the expected Greek (or Roman) attire, they wear garments that also speak to Egypt's antiquity. The man wears only a shendyt-kilt, belted about the waist, known from Old Kingdom royal portraits and a type that is characteristic of the archaizing sculptures of Dynasty Twenty-six and Twenty-seven for nonroyal persons. It is one employed variously in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods and corresponds, too, to the type of kilt awarded the Emperor Hadrian's favorite, Antinous, in posthumous portraits that fashion him as pharaoh. The woman is clothed in a diaphanous garment that hugs her body and bares her ankles in a length that would be otherwise unseemly for a Greek (or Roman) matron. With their pose and garments, then, these patrons assume an intentionally Egyptian aspect. Simultaneously, however, with their portrait heads, they retain not only their Roman identity but also the specificity of their individual identity, for – despite their Egyptian pose and garb – these statues indeed appear as true portraits. The seeming verisimilitude of their faces distances these figures from all other images in the sculptural program of the tomb. It underlines the impulse toward individuality rooted in the Hellenistic world that flourished in Rome and the regions it influenced, and this verisimilitude separates these statues from Egyptian ‘portrait’ types.

The doorway to the burial room – the naos or chapel of the temple-tomb – is flanked by Agathodaimons (‘good daemons’ in the form of snakes) which mirror one another. They face inward toward the opening to the burial room as they coil themselves atop stands that assume the form of a truncated Egyptian naos. Each snake is capped with an Egyptian pschent crown, signifying its connection to royalty, for in Alexandria the Agathodaimon received both public and private cults. But these Agathodaimons also each support a Greek thyrsus and a Greek kerykeion in its coils. The kerykeion (caduceus), a signifier of Hermes, is a common attribute of Agathodaimons on coins of Roman emperors, but the thyrsus is rarely, if ever, pictured with Agathodaimons elsewhere, and the coupling of the two staffs is unexpected. As the kerykeion connects the Agathodaimons with Hermes, the thyrsos connects them with Dionysos – two deities that engage multiple eschatological functions.

Within mortuary context, the kerykeion recalls Hermes as psychopompos, who leads the dead to the skiff that traverses the river Styx, and to Charon its navigator; it also connects to Hermes as chthonios, who harrows the Underworld at will. The thyrsos, for its part, activates the chthonic aspect of Dionysos, recalling his mysteries and his importance in afterlife religion celebrated, for example, on ‘Orphic’ gold leaves. Diodorus Siculus (Bibl. 3.65.6), writing in the first century bce, considered Orphic mystery rites the same as Dionysiac, and ‘Orphic’ gold leaves – which preserve poems found in mortuary context once attributed to Orpheus – confirm the connection. One ‘Orphic’ gold tablet, for example, which sets out directions for the journey, ends:

Notably, a relatively large share of Alexandria's early population derived from regions in which ‘Orphic’ gold leaves or ‘Orphic’ texts can be attested, and furthermore it has been persuasively argued that the Grand Procession of Ptolemy II, which was recorded by Kallixeinos and which must have taken place in Alexandria some time in the early 270s bce, carried ‘Orphic’ elements on its floats. It is possible, too, that the library at Alexandria, given the breadth of its holdings, contained scrolls with ‘Orphic’ texts.

In addition to their connection to Hermes and Dionysos, the Agathodaimons provide a formidable presence at the entrance to the tomb. Their role as guardians is emphasized by the Greek hoplite shields carved in low relief on the wall above them that bear apotropaic gorgoneions set within winged quatrefoils. The Agathodaimons on the exterior wall of the burial chamber provide an introduction to their protective counterparts on the corresponding interior wall of the room and render double protection for those deceased entombed within the sarcophagi of the burial room.

The Burial Room

Responding to the protective images on the exterior of the burial room, Anubis, the Egyptian guardian of the necropolis, is seen in two different aspects on the interior entrance wall of the room. Poised to either side of the doorway, the images of Anubis face toward the opening posed on the same sort of egyptianizing naos-like stands that support the Agathodaimons on the other side of the wall. One version of Anubis sees him as anthropomorphic, the other as anguiped, but although the form of the deity differs, the poses mirror one another, and each aspect is garbed in military dress.

The version of Anubis with the head of a jackal and a human body stands frontally in a differentiated pose with his weight borne by his left leg and with his head, crowned by a solar disc, turned to his right (. Assuming the pose developed for Hellenistic rulers and appropriated for Roman emperors, he holds in his upraised left hand a spear or scepter, on which he leans his weight, and with his lowered right, he holds a shield that rests on the ground. He wears a muscle cuirass with pteryges (flaps) over a short chiton and has a short sword suspended at his left hip from a baldric over his right shoulder.

Anubis in military garb is a relatively common Roman reinterpretation of the Egyptian guardian of the necropolis, although the meaning of the image is problematic. Henri Seyrig takes the military garb as apotropaic, whereas Jean-Claude Grenier and Jean Leclant give it the double meaning of protection and victory over death, and Ernst H. Kantorowicz and Roberto Paribeni see it taking its model from emperors and therefore incorporating regality. In the context of the image in the burial room of the Main Tomb, any, or all, of these interpretations may be correct.

The anthropoid Anubis at Kom el-Shoqafa and a similarly garbed and posed Anubis that appears on the piers of the painted Roman-period Stagni tomb from Alexandria's western necropolis demonstrate one aspect of the sophisticated bilingual style that contiguity with Egypt encouraged. In these images, the deity assumes his normal Egyptian cynocephalic human form, but he dresses the part of a Roman legionary as he assumes the chiastic pose that is the hallmark of classicizing sculpture. In pose, garb, and execution, the Egyptian guardian of the necropolis is refashioned in Roman terms, but he also takes on an extended meaning as his assimilation to a Roman centurion – a Roman guard, as it were, – at once reiterates and broadens his Egyptian function. This bilingualism recalls the similar iconographical efficiency of the Egyptian sphinxes crouching before the main facade in the tomb Moustapha Pasha 1 and the doorways of Anfushy Tomb II and the ba-bird of the Sāqiya Tomb. Despite the Classical heritage each acknowledges, each references Egyptian signs and symbols to create a new and more potent image of supernatural protection for its tomb.

The other entrance wall of the Main Tomb shows a more exceptional version of Anubis: he is in similar martial form but with a snaky tail instead of human legs . Garbed similarly to the anthropoid Anubis, he adds only a short chlamys pinned on his right shoulder and replaces the solar disc with an atef crown. He holds a spear in his upraised right hand and grasps the end of his chlamys with his left. Despite (or perhaps because of) his uncanonical form, this figure must be the primary one of the two because he supports his weapon in his correct right hand. The image of an anguiped Anubis is very rare, but not unknown beyond his depiction in the Main Tomb, though none finds Anubis garbed as a Roman legionary. Nevertheless, Anubis in anguiped form is exceptional, and the snaky-legged Anubis as a Roman soldier is currently unique to the Main Tomb, where he responds to and reiterates the function of the Agathodaimons on the exterior wall. The image exemplifies – as does the abduction of Persephone in the ‘Hall of Caracalla’ niche – the iconoclastic creativity of the Alexandrian artists. It stands as yet another example of the intentional integration of Roman and Egyptian conceptual and formal elements employed by Alexandrians to produce a new means of expression in a city whose population had accumulated the knowledge to address this complex past. These images of Anubis (and the ones on the piers of the Stagni tomb) also perpetuate the ancient Greek tradition of ‘monsters’ guarding the tomb, seen in Alexandria in the sphinxes in Moustapha Pasha Tomb 1 and Anfushy Tomb II, the ba-bird of the Sāqiya Tomb sarcophagus, and the Agathodaimons and gorgoneion shield emblems on the exterior of the burial chamber of the Main Tomb.

The plan of the burial chamber of the Main Tomb, in consonance with the generally Classical plan of the entire tomb, assumes a Roman form. Trabeated niches (but with arced ceilings) cut into its walls create its cruciform plan, and a rock-cut sarcophagus set into each of the niches gives the room its triclinium aspect. Apart from being a Roman modification of the kline chamber, and in addition to the triclinium form specifically identifying the sarcophagi as metaphorical banqueting couches as suggested earlier in this chapter, other considerations may also have prompted the cutting of triclinium-shaped burial rooms in Roman-period tombs. Certainly, the Great Catacomb's real, usable triclinium fitted out with rock-cut klinai near the tomb's entrance demonstrates the importance of the funerary feast that took place at the tomb and the memorial meals that would have occurred during the year in commemoration of the dead, and the Totenmahl reliefs – one of the standard motifs for Roman gravestones in the Egyptian chora – which, by placing the deceased at a hero's banquet, heroized him or her, may have propelled the eschatological impulse to memorialize the banquet of the dead in architectural form.

In contrast to the triclinium plan, but in concert with the Egyptian architectural elements in the pronaos of the tomb, each of the three niches of the triclinium-shaped burial chamber is defined by engaged piers carved to repeat those of the antechamber. Yet antithetical to the architectural framework of the niche, each niche in the Main Tomb encloses a fully realized Roman garland sarcophagus, and each narrative that enlivens the walls of the niches is framed above with a Classical egg-and-dart motif. Nevertheless, complementing the piers, the figural decoration of the Main Tomb is also egyptianizing. Consonant with the two versions of Anubis on the entrance wall that fuse Egyptian and Graeco-Roman traditions, egyptianized narratives decorate the back and side walls of the niches above the Roman sarcophagi, according the niches their bilinguality.

The symmetry of the cruciform-shaped room is emphasized both by its figural decoration and by the treatment of the sarcophagus facades, for though all the sarcophagi are carved as garland sarcophagi, details of the garland of the central sarcophagus differ from those of the other two. Their major motifs remain the same, however, and the duplication of these motifs underscores the intention of the ornament: all sarcophagi show frontal heads (or masks) of apotropaic figures. The central sarcophagus fastens a gorgoneion and a frontal satyr head to the circlet that pins the garland to the wall and the lateral ones fix two gorgoneions to the background wall in the semicircles created above the swags. Protective devices thus reach their apogee in the Main Tomb, which is multiply protected by the gorgoneions emblazoned on the hoplite shields and the Agathodaimons on the exterior of the chamber, the two versions of the militaristic Anubis facing the doorway on the chamber's interior wall, and the gorgoneions and satyr masks on the room's sarcophagi.

In accord with the details of the sarcophagus decoration, the Main Tomb's symmetry is further enhanced by the figurative treatment of the walls of the niches. Recalling the upper scenes on the back walls of the Persephone tombs in the Nebengrab, as well as those depicted in other tombs in Alexandria, the back wall of the Main Tomb's central niche shows the lustration of the mummy Nevertheless, despite the frequency of the lustration scene in the tombs at Kom el-Shoqafa and elsewhere in Alexandria, few mummies are found in the catacombs at Kom el-Shoqafa, and few mummies – or traces of mummies – have been found in Alexandria at all. Unlike elsewhere in Roman-period Egypt, in Alexandria the appropriation of mummification is not based on the physicality of mummification but on the use of the imagery of mummification – and often its extended narrative – to visualize Greeks’ own concepts of the afterlife.

In contrast to the frequency of the theme of the back wall of the central niche in Alexandria, the back walls of the left and right niche – which are almost perfect mirror images of one another – show scenes that are unique in Alexandria. Each lateral niche embraces an image of the Apis bull standing on a truncated naos-like pedestal. He is sheltered by the wings of Isis-Ma'at who stands behind him, holding out the ostrich feather of truth in her farther hand. In front of him, across a small altar, a male in a kilt and corset, a short mantle slung across his neck, and wearing a pschent crown holds out a decorated collar Unless the royal crown is used cavalierly, the male figure should be an Egyptian pharaoh or a Roman emperor in his Egyptian manifestation.

Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Back Wall of Right Niche

Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Back Wall of Left Niche

Though the central niche is privileged by its unduplicated subject, compositionally uniting the three scenes on the back walls of the niches is their general bilateral symmetry, although the Apis bulls, which face toward the rear of the tomb, permit the scenes on the left and right walls to appear directional. All scenes admit anomalies, but none of these deviations are especially out of place in a Roman-period context.

In contrast to the back wall of the central niche, which is singled out by its subject, the lateral walls of all the niches are treated similarly. All admit symmetrically disposed two-figure compositions, though the characters depicted and their gestures differ, and all the figures face one another across an altar that is raised on variously shaped stands.

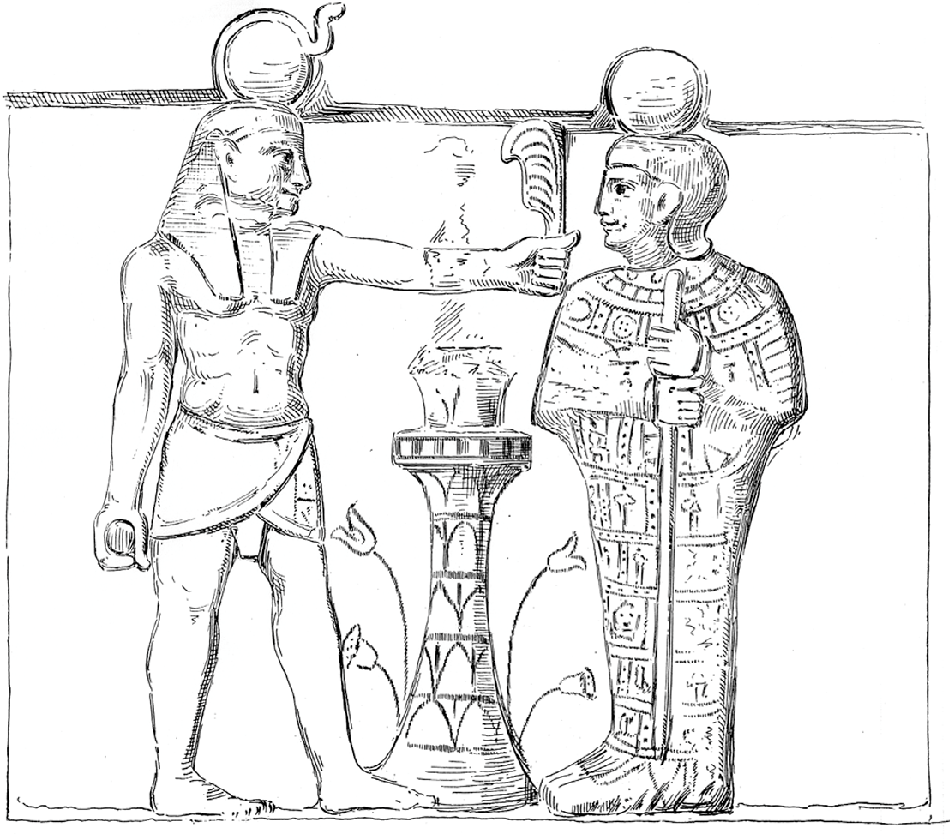

The left wall of the central niche depicts a male figure facing a priest across the altar, on which a fire burns within a cylindrical vessel, probably filled with incense The male figure, crowned with a solar disc, wears only a long garment bound about his waist. In his right hand he holds out an object difficult to interpret; it appears to be flexible and soft, and although it does not precisely replicate the traditional Egyptian form, it might be the ubiquitous srips of linen – “fabric bands that signify rebirth” – that mortuary figures often hold. He bends slightly and awkwardly from the waist and raises his left hand to his face in the Greek male gesture of mourning. Behind him is a partial cartouche with pseudo-hieroglyphs that reoccurs in all the two-figure scenes. Opposite the mourning male, a lector priest, barefoot and wearing a long, wrapped garment with a panther skin draped over it, holds up a scroll from which he reads out the appropriate spells.

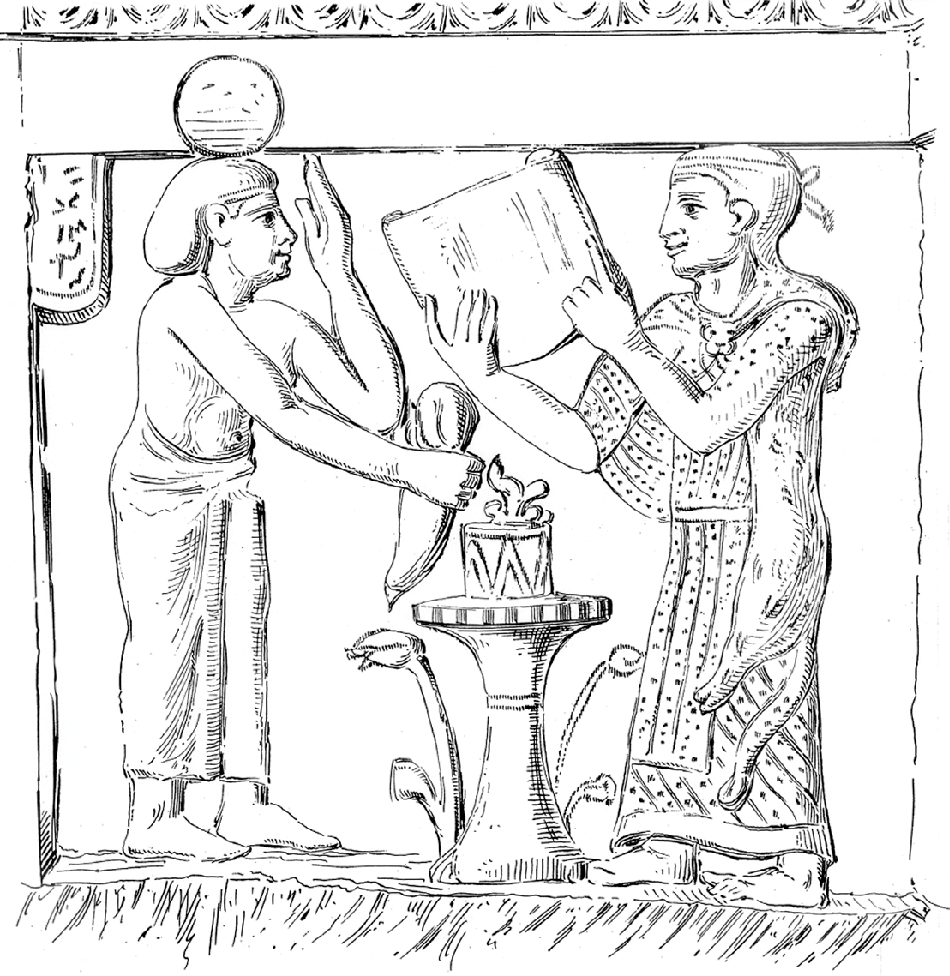

The priest on the right wall of the central niche faces a woman across the altar . The two feathers the priest wears in his headband identify him as a pterophoros (wearer of feathers), a hierogrammatos or sacred scribe in the cult of Isis.Like the priest on the left-hand wall, he wears a long garment, but his is slightly shorter, of thicker cloth, and differently arranged and decorated, and the animal skin that denotes his office is also differently draped. He holds out a lotus (?) in his right hand and extends a plate that supports a spouted lustration vessel in his upraised left. The woman who faces him across the altar wears a layered wig and a long, clinging, fringed garment that permits a view of her body underneath. Like her male counterpart, she is crowned with a solar disc.

2.24. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Right Wall of the Central Niche

The scenes on the side walls of the lateral niches present other characters, and, like the scenes on their back walls, they correspond to one another, though they lack the almost perfect mirror-imaging of the scenes at the rear of the niches.

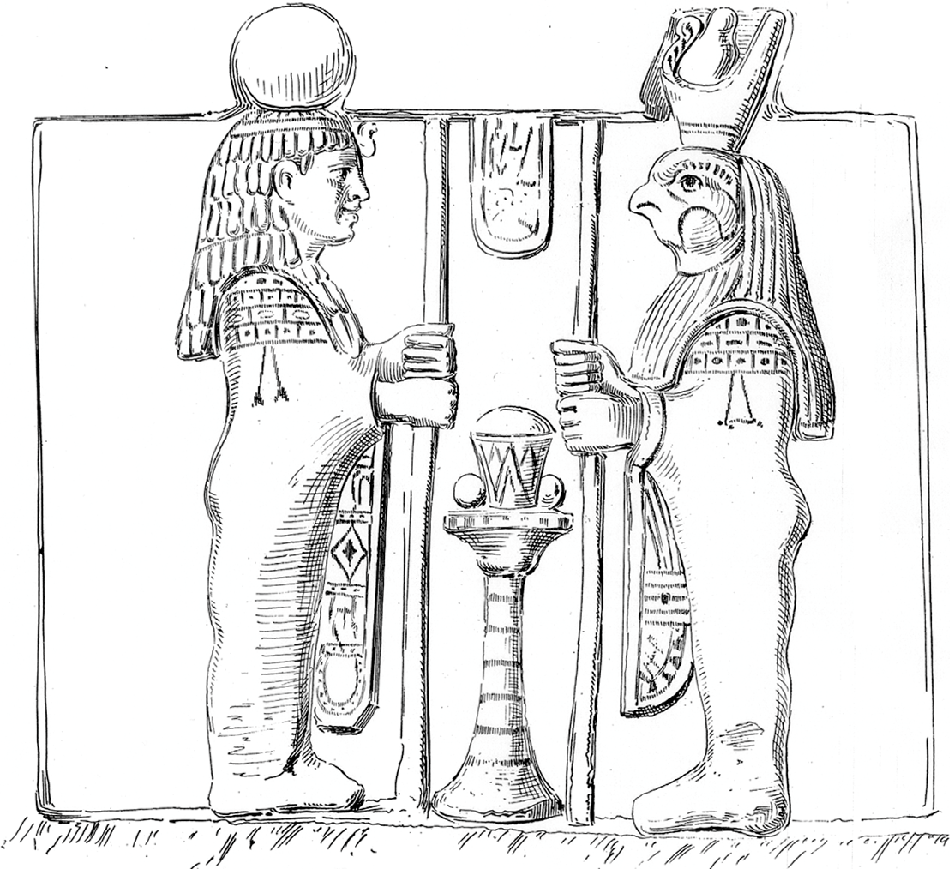

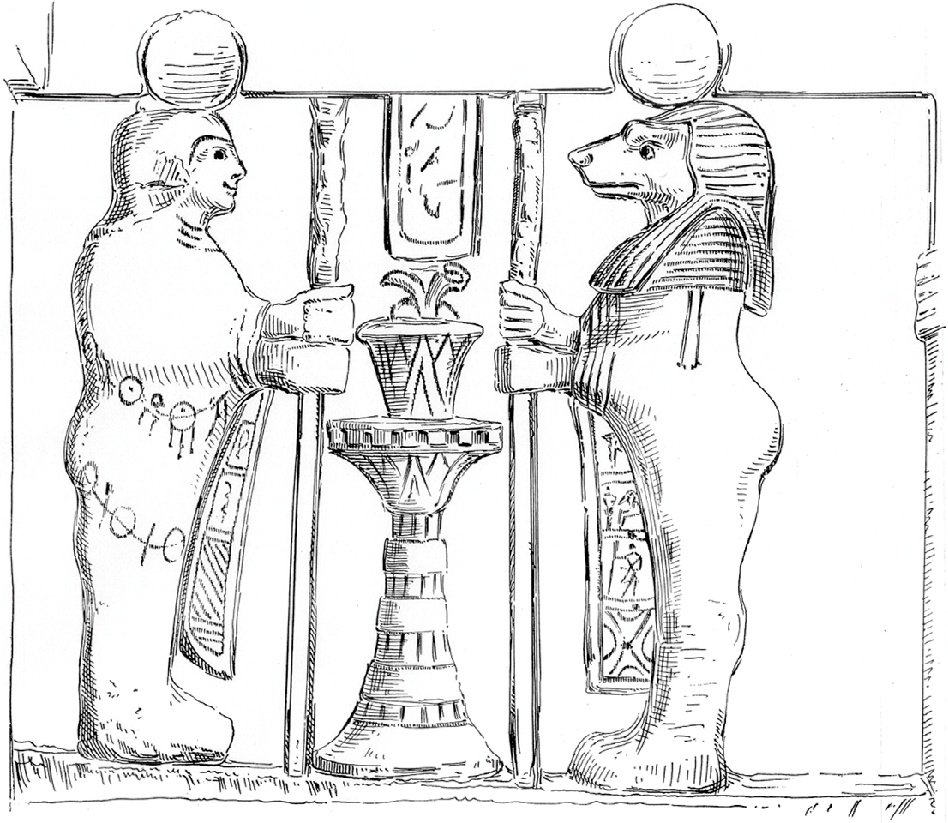

On the left wall of left niche, a female wrapped in a tight garment faces the falcon-headed son of Horus, Qebehsenuef, who wears a pschent crown . Unlike most of the figures in the confrontations on the short walls, these figures are in true profile. Each figure holds a scepter in hands that emerge from its tightly wrapped garment, and each has a decorated swath of fabric pulled tightly across its shoulders that falls vertically in front of its body so that its decoration is visible. Sons of Horus normally do not wear crowns or hold staffs, but Qebehsenuef's crown and scepter accord with the generally regal tone encountered throughout the imagery of the Main Tomb. The female figure wears a layered wig and a band fronted by a uraeus across her forehead, and she is crowned with a solar disc like the male and female in the lateral walls of the central niche. Rowe interprets her as Isis, but given the symmetry of the decoration, this figure – which corresponds to a male figure directly across the tomb on the right wall of the right niche – is unlikely to be an Egyptian deity, and the solar crown demands another explanation.

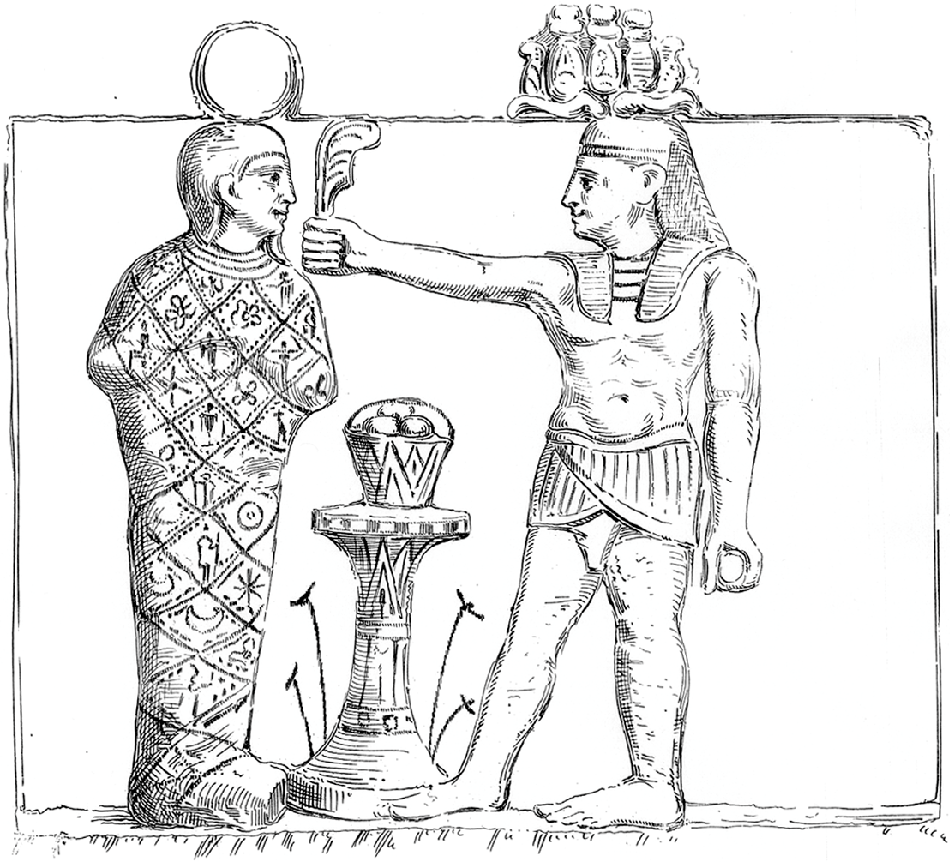

On the right wall of the left-hand niche, a figure that is completely mummiform faces a pharaoh, who is nude but for a shendyt-kilt, a pectoral, and a nemes capped with a hem-hem crown . The pharaoh holds the rolled cloth of authority in his lowered left hand, which is no longer extant, and extends the feather of Ma'at toward the mummy with his right. The male mummy-like figure, who wears a false beard and is crowned with a solar disc, stands properly in the Egyptian composite stance with his face and feet in profile and upper body frontal, but remarkably his arms and joined hands appear plastically indicated beneath his garment. The garment itself is crossed with a diamond pattern, a simplification of the reticulated bandaging characteristic of Roman-period mummies, and in each diamond-shaped coffer, varied signs seem to denote bodies associated with the celestial realm.

2.26. Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Right Wall of the Left Niche

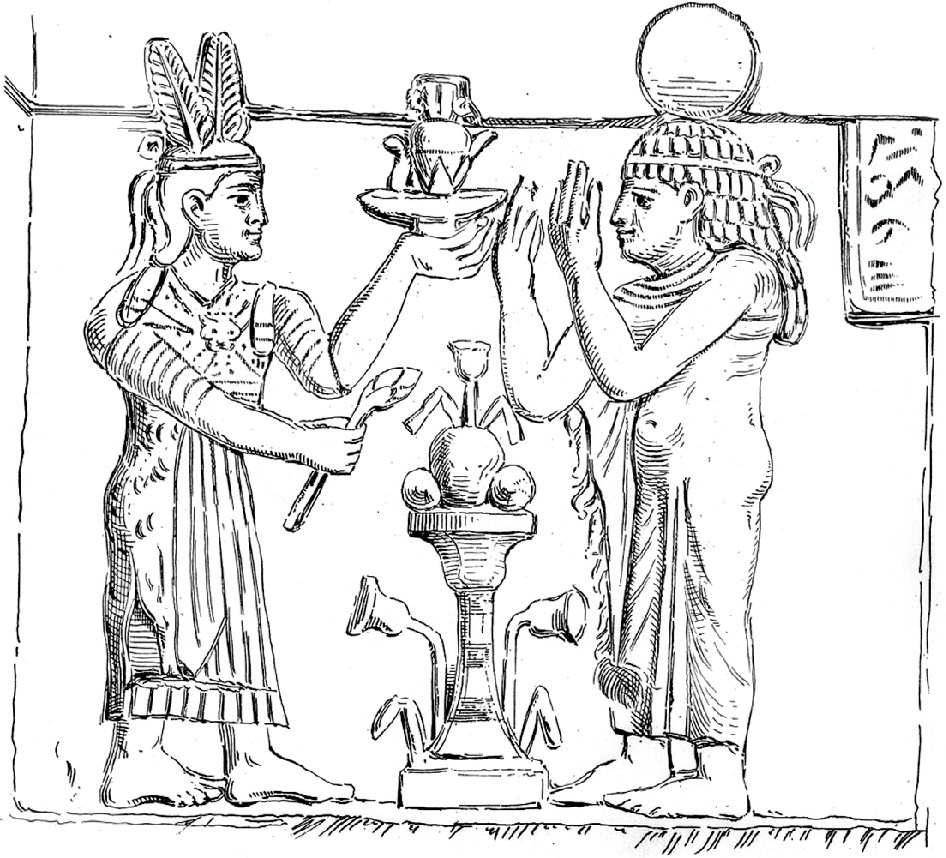

The composition of the left wall of the right niche mirrors that of the right wall of the left niche . although the details differ. The pharaoh, or Roman emperor in the guise of pharaoh, is crowned with a solar disc fronted by a uraeus instead of a hem-hem crown, and he extends the feather of truth to a mummiform figure who holds a staff in his hands. This figure stands in the same composite pose as the one of the right wall of the left niche, but his hands emerge from his mummiform cloak to grasp a staff. In contrast to the garment of the first mummy-like figure, his garment is patterned with a horizontal-vertical grid – one that is also employed to distinguish mummy bandages – which contains less-readable signs in the boxes created.

Alexandria, Kom el-Shoqafa, Main Tomb, the Burial Chamber, the Left Wall of the Right Niche

The right wall of the right niche follows the structure of the left wall of the left niche . A mummiform male figure faces Hapy, the baboon-headed son of Horus, both figures confronting one another in true profile stances. Both are crowned with solar discs, and both have decorated swaths of fabric falling vertically in front of their bodies, as do the figures on the left wall of the left niche, but the male adds two strings of amulets looped across its lower body. Alan Rowe identifies the male figure as Imsety, another of the sons of Horus, but this identification is improbable. The lateral scenes in the side niches correspond so closely to one another that it would be remarkable if the male were meant as Imsety (or any deity), given the complementary female figure that he parallels.

Clearly a strongly symmetrical structure underlies not only the architecture of the burial room, but also constitutes the impetus behind its pictorial program. The lustration scene of the central niche is flanked to left and right by priests facing human figures, a male on one side and a female of the other. Both male and female face inward, toward the back of the niche and, consequently, toward the back of the tomb. The side niches complete the symmetrical arrangement, for not only do the central scenes of the lateral niches mirror one another, but a direct correspondence between their left and right walls augments the symmetry. Hapy and Qebehsenuef are paired across from one another on the lateral walls closest to the entrance to the tomb. The two mummy-like figures face one another across the royal figures that engage them and who stand back to back across the room. This precise conceptual parallelism demands that a unified program must govern all the figured scenes in the niches.

In Monumental Tombs of Ancient Alexandria, I argued for the identification of the ‘emperor’ in the large panels in the lateral niches as Vespasian. It is indeed possible that Vespasian is honored here, but Rowe, more perceptively, sees the emperor on the left wall of the right niche who wears the solar-disc crown as deceased and the one who wears the hem-hem crown as his live successor. I now think, however, as is evident from my description of the scenes, that the precise identity of the royal figure may be of less consequence than his station, and I address this concern later. In Monumental Tombs, I followed, to a great extent, Rowe's identification of the nonroyal figures on the walls of the Main Tomb, but I now think that neither he nor I was correct. Jean-Yves Empereur initially queried the identity of the mummy-like figure with the staff as other than a mummy, and I discounted his interpretation, noting that he had ignored the figure's staff. With respect to his perspicacity, I should like to revisit the identification of the all the figures in the room in an attempt to unravel the meaning of the sculpted program of the burial chamber.

The iconographic treatment of the deities Horus and Thoth in the central niche indicate that the designer of the tomb's imagery was fully cognizant of the principles of traditional Egyptian representation. It may be surprising to see the two deities flanking the bier – Isis and Nephthys would be a more likely pair – but by the Roman period, Horus’ and Thoth's appearance in lustration scenes is well documented, and though both deities wear crowns that may appear exceptional, these headdresses can also be paralleled elsewhere. The knowledgeable iconographical treatment of figures in this scene speaks against Rowe's identification (that I had previously followed) of the mummiform figures on the side walls of the lateral niches as Osiris and Ptah, since these figures lack their normal identifiers, and the symmetrical presentation in the central niche and elsewhere in this tomb argues for a coherent program.

I now take these mummiform figures as the deceased patrons of the tomb. This identification is buttressed by the mummiform figures that represent the deceased in House-tomb 21 at Tuna el-Gebel, the tomb of Petosiris at Dakhla (both discussed in further chapters), that of Qtjjnws in Ezbet Baschandi, and elsewhere. At Kom el-Shoqafa, the female mummiform figure facing Qebehsenuef on the left lateral wall of the left niche (Rowe's Isis; wears the same wig as the female facing the pterophoros in the right lateral wall of the central niche ; the male on the right wall of the right niche (Rowe's Imsety), who faces Hapy wears a hairstyle similar to – though not precisely the same as – that of the male on the left lateral wall of the central niche . Each of the four male and female figures, whom I now take as human, is crowned with a solar disc, and I suggest that the male and female mummiform figures on the side walls of the lateral niches are intended as the same individuals as those on the side walls of the central niche. I further propose that the solar-disc crown designates not only deities and the dead but also the dead as assimilated to Re and therefore as accorded a celestial afterlife.

The two humans on the walls that flank the central niche are the only nonroyal, secular, human figures that do not assume the stance of a mummy: they stand in a quasi-three-quarter view as they raise their hands to the priests who face them. Aside from the solar discs that crown their heads, their wigs and their garb appear unremarkable, though the garments of both the male and female can be paralleled in figures associated with the cult of Isis. The woman's garb is similar to the mantle worn by Isis and female initiates into her cult, though she lacks the Isiac undergarment; the male's long kilt wrapped around his waist, though more generic, also marks out adherents to the cult. The lector priest that faces the male initiate is (with the sem-priest) the priest that traditionally officiates at Egyptian funerals. The pterophoros that faces the female initiate, however, as previously noted, is connected specifically with Isiac rites that offer a blessed afterlife. And a blessed afterlife appears to be the unifying theme throughout the tomb. The mortal figures bearing solar crowns inhabit the celestial realm. Based on the appearance of the pterophoros and the garments worn by the male and female who address the priests on the side panels of the central niche, they achieve this state because of the beneficence of Isis and their initiation into her cult.

The repetition of male and female in the lateral niches and the equal weight afforded them within the imagery of the chamber correspond to the equal weight given to the representations of the figures in the niches in the pronaos of the tomb. One detail, however, yet to be mentioned, suggests that the woman is the primary recipient of the chamber, for in addition to its garlands and masks, the central sarcophagus shows a female figure reclining upon a mattress set on a pallet above the pendant garland The woman's garment falls off her left shoulder in a mark of motherhood. The figure replicates the reality of Roman matrons reclining at a banquet and the mimetic motif of Roman women reclining on the lids of their sarcophagi, and presumably for this latter reason, Rowe correctly identified her as the deceased. The syntax of the chamber that places her directly below the mummy in the scene above strengthens Rowe's supposition, and though the mummy may be depicted as a male, this kind of gender-bending does not seem foreign to treatment elsewhere If indeed this woman is the primary recipient of the tomb, she would be one of the few women whose luxury burial in Roman-period Alexandria can be identified.

Comments

Post a Comment