new study shows that Tutankhamun,

Egypt’s famous “boy-king” who died around the age of 18, suffered a

“massive crushing tearing injury to his chest” that likely would have

killed him.

new study shows that Tutankhamun,

Egypt’s famous “boy-king” who died around the age of 18, suffered a

“massive crushing tearing injury to his chest” that likely would have

killed him.

X-rays and CT scans have previously shown that the pharaoh’s heart, chest wall, the front part of his sternum and adjacent ribs, are missing. In Ancient Egypt the heart was like the brain and removing it was something that was not done.

“The heart, considered the seat of reason, emotion, memory and personality, was the only major organ intentionally left in the body,” writes Dr. Robert Ritner in the book Ancient Egypt.

The new research was done by Dr. Benson Harer, a medical doctor with an Egyptology background, who was given access to nearly 1700 CT scan images of Tut that were taken by a team of Egyptian scientists in 2005. Dr. Zahi Hawass, head of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, gave permission for the work.

“Zahi was very kind he let me get access to the entire database of all the CT scans,” said Dr. Harer.

It has been suggested that tomb robbers, operating sometime between 1925 and 1968, may have stolen the heart and chest bones. The new research shows that while robbers stole some of Tut’s jewellery they didn’t take the body parts. Instead they were lost due to a massive chest injury Tut sustained while he was still alive.

This isn’t the only medical problem Tut had. In 2005 a team of researchers reported that he had a broken leg and earlier this year an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association revealed that Tut suffered from malaria, something that may have contributed to his death.

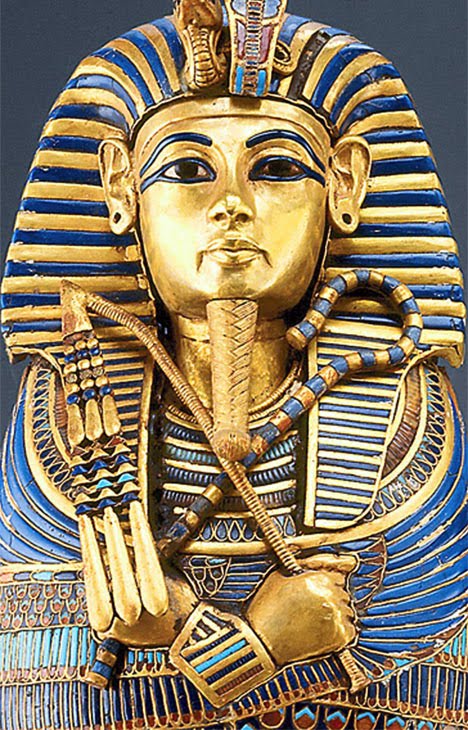

This treasure from Tut's tomb shows him harpooning what is believed to be a hippo. Photo by Sandro Vannini

Harer specializes in Obstetrics and Gynecology, but also taught Egyptology as an adjunct professor at California State University at San Bernardino, up until his retirement.

1968 - The first X-rays

To understand what happened to Tut’s chest we need to go back to 1968. In that year the first x-rays were done revealing that many of Tut’s chest bones were missing. They also showed that jewellery, which had been on King Tut when an autopsy was done in 1925, were also gone. This means that robbers got to him sometime between those years.Harer’s research indicates that while Tut’s jewellery was certainly stolen, the chest bones were already long gone.

The CT scans show, in high-resolution, the edge of what is left of Tut’s rib bones. Dr. Harer said that “the ribs are very neatly cut” and could not have been chopped off by modern day thieves. “The ribs were cut by embalmers and not by robbers.”

He added that “if you try to cut through a 3,500 year old bone it is brittle, before you can saw up through it the pressure on the bone would crack a vast part and you would have jagged edges of the bone,” he said.

“These are neatly trimmed and the robbers are not going to take the time to try and do a tidy job.”

King

Tut's mummy, as photographed by Harry Burton, the photographer that for

Howard Carter documented the opening of Tutankhamun's tomb. - Image

copyright the Griffith Institute

embalmers

used to take out his intestines, liver and stomach.

In Ancient Egypt those organs were removed after death and put into canopic jars (video: King Tut's canopic shrine and jars introduced).

embalmers

used to take out his intestines, liver and stomach.

In Ancient Egypt those organs were removed after death and put into canopic jars (video: King Tut's canopic shrine and jars introduced).Harer said that the embalmers used a “transverse incision” which was cut into Tut and went from his umbilicus (his navel), towards the spine. They “took out the organs below the diaphragm,” he said. However “they did not go through the diaphragm to extract the lungs - the chest was gaping open, they could just lift them out directly.”

Harer says he has never seen another royal mummy cut into this way. “Tut is the only upscale mummy I know that had a transverse incision.”

Normally, for religious reasons, there would be “a special amulet, an embalming plate, over the incision that the embalmer made.”

However, in this case, there is none. “Since the body already had a huge opening – it would be pointless to suture the abdominal incision and protect,” Harer wrote in his journal article.

Also Tut's arms were crossed at his hips, not at his chest, as would normally be befitting a pharaoh.

Stuffing up Tut

There’s more evidence that Tut's chest, including the skin, had been gouged away while he was still alive.When the first autopsy on Tut was done in 1925, it revealed that he had been stuffed like a turkey, filled with what Howard Carter called a “mass of linen and resin, now of rock-like hardness.”

Harer says that the CT scans show that this material would have been packed from the chest down.

“The chest was packed first, and as they did so, they pushed the flaccid diaphragm down – they inverted it,” said Dr. Harer. However the packing improved the appearance of Tut’s chest, “the packing restored the normal contour of the chest and then the beaded bib (with Tut’s jewellery) was placed on top of it.”

When Carter examined the bib he was impressed with how adherent it was. "It was so adherent that he couldn’t successfully remove it,” said Harer. Carter didn't hesitate to remove other parts of Tut's body, he actually hacked off the limbs in order to aid the autopsy.

Harer pointed out that if the bib had been put over Tut's skin (rather than the packing material) he should have had no trouble with it. “If that beaded bib had been placed over skin over the clavicle, the skin would have provided a plane in which the bib could have been easily removed.”

Chased by Hippos - Watch towards the end of the video, where you'll see a hippo ferociously attacking a boat.

What caused this injury?

One possibility that Dr. Harer ruled out is that of a chariot accident. “If he fell from a speeding chariot going at top speed you would have what we call a tumbling injury – he’d go head over heels. He would break his neck. His back. His arms, legs. It wouldn’t gouge a chunk out of his chest.”Instead, at his Toronto lecture, Harer brought up another, more exotic possibility - that Tut was killed by a hippo.

It’s not as far out an idea as it sounds, hippos are aggressive, quick and territorial animals, and there is an artefact in Tut’s tomb which appears to show him hunting one of them.

It would also explain why there is no account of Tut’s death since being killed by a hippo would be a pretty embarrassing way for a pharaoh to die.

“Hippos kill more people than any other animal, they are the most lethal animal in Africa (if not) the world,” said Harer. “The victim suffers massive tearing injury and can actually be cut in half.” Medical reports indicate that “even though they are running away from the hippo they typically suffer a frontal wound.”

In Tut’s case, if the hippo charged, his entourage may not have been able to get to him in time. “If he did have a club foot (as a recent medical report suggests) it would make him the slowest person getting out of the way – the easiest person for the hippo to get.”

Tut may not have even been hunting a hippo. “It may have been that he was fowling in the marsh, just got in the wrong area, and the hippo attacked him.”

Still, it's tempting to imagine Tut trying to hunt a hippo. Despite his club foot and malaria, it's enticing to believe that the teenage pharaoh decided to hunt one of the most dangerous animals in the world. If his goal was to increase his fame then he succeeded far beyond expectations, in death becoming the most famous Egyptian ruler who ever lived.

Comments

Post a Comment